Authors: Merel van der Vaart and Areti Damala

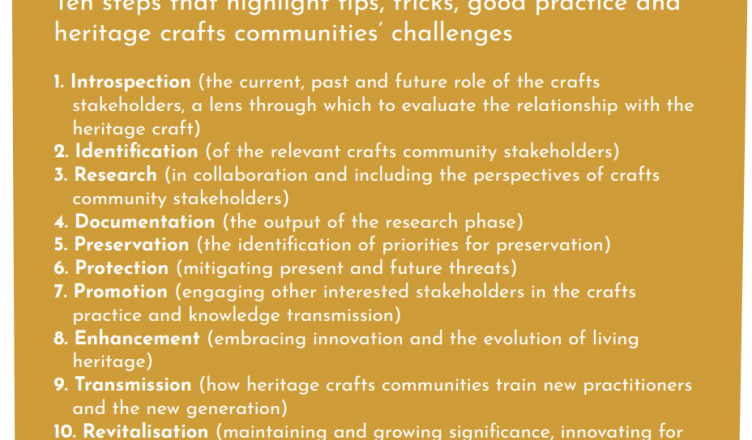

Drawing from the wider literature and our experience in the Mingei project, we set out a series of ten steps that highlight tips, tricks, good practice and Heritage Crafts-specific challenges. The advice is structured based on the 2003 ICH definition of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage but starts with an extra preparatory step: introspection. From introspection we take you on a journey of working with Heritage Crafts Communities, through research and preservation to promotion and revitalisation. To explore each of the ten steps, we illustrate it with good practice drawn from case studies from Mingei and from our research.

1. Introspection

Before reaching out to craft communities, it is important to understand the role and position of your institution, now and in the past. Take a moment to examine the way your organisation has represented and engaged with crafts in the past up until today. If you are an organisation that looks after tangible cultural heritage related to Heritage Crafts, look at your collections. Where are crafts present in your collections and how are they described or labelled? For example, does your organisation refer to them as applied arts or folklife? Understanding the lens through which the organisation you work for has collected, studied and interpreted crafts will help you see what perspectives might be missing. Through introspection, you can better understand the relationship your organisation had with craftspeople in the past, while also anticipating how you might be viewed by Heritage Crafts communities today.

2. Identification

Do you have a clear understanding of the diversity within or among the communities related to the Heritage Crafts you are working with? Try to list all the people involved in the craft and differentiate between Heritage Crafts communities and stakeholders.

Once you have done this, do some desk research to find out who the key people might be who could introduce you to the community. Always make sure if a person you consider to be a representative of the community is indeed capable of representing it. Try to understand what this person’s motivation might be to take on this role of representative. Do they have an alternate agenda? Ask for introductions to other community members and make clear you find it important to better understand the diversity within the community. If a person is unwilling or unable to make these introductions, it is probably important to better understand why this is the case. Stay aware of potential alternative stories or diversity within the community while you conduct your work.

In most cases, it will be impossible to meet with all the members of a Heritage Crafts community, but when deciding how to invest your time, ask yourself these three questions:

- Do you have a clear overview of all the different Communities related to this Heritage Craft? Think about practitioners of the various stages of the craft, formal or informal students, and others who are directly affected by, though not participating in the craft.

- Who are the key representatives of these different communities?

- What are events or places where you could informally meet a wide range of community members, as an opportunity to identify more relevant partners?

3. Research

Most Heritage Crafts can be researched through desk-based research to a point. Historic and contemporary descriptions, videos, photographs and other physical materials related to the craft might help you get a sense of it. But because Heritage Crafts consist of tangible and intangible heritage, a lot of the research can only take place in collaboration with Heritage Craft Communities. Firstly, it is important to understand the status of the craft among these communities. Does their view of and valuing of the craft match that of the documentation you have studied? Or do you see differences that need to be further explored?

For the Mingei project, we are exploring how to digitise both the tangible and intangible elements of Heritage crafts. To do this, the technical and heritage partners on the team have identified the many different elements that could be studied to create a good understanding of each craft. Physical items are materials, artefacts, manufacturing tools or machines, protective or traditional clothing relevant to the craft, as well as the workspace(s). Craft practices encompass actions of the practitioner(s), which means our research should not be limited to ‘things’, but should also include the bodies of the practitioners, as well as their motions. It is clear that this research cannot be done in any other way other than in collaboration with practitioners. Craft understanding involves the identification of craft processes, separating them into activities and actions, the spatial and physical expression of craft processes, their temporal organisation, as well as the identification of the involved objects and actors.

When it comes to understanding the craft fully, we also have to identify points where decisions are being made in the process, alternative techniques, and the correction of mistakes. We have to understand if the craft is changing, and if so, how. If you want to describe a craft, you would need to collaborate with Heritage Craft Communities to develop a vocabulary of terms, verbal definitions, and visual descriptions that should include the materials, tools, and products of a craft. Holistically approaching a Heritage Craft creates a lot of data. These data need to be organised in terms of craft roles and steps, the materials and the actions used. This organisation of data needs to work with the tools or machines that you will use to map the craft tasks and processes.

Working with Heritage Craft Communities in your research phase can take many different forms. Depending on the situation, you might choose or be able to use techniques that allow for more or less active engagement. Techniques you could use include co-creation, ethnography, participant observation and interviews.

4. Documentation

The output of the research phase is documentation. As research methods vary, so too will the type of documentation you produce. The primary output may be in the form of notes, images, audio-visual recordings, reports, etc., that describe the operational part of the process or stories relating to the socio-historical context of the craft. We propose the use of storyboards to organise the output of this process as a useful tool for (a) illustrated scripts that separate actions into simpler ones and (b) validating this transmitted information with the craft community, collecting feedback, and identifying parts of the process that may be underrepresented. Storyboards can contain temporal arrangement, visualisations, verbal description of actions and activities, and identify the involved objects and actors.

5. Preservation

To understand how a Heritage Craft can or should be protected it is important to understand the past, current and future threats facing the craft. Heritage Craft Communities are best placed to understand these threats. Is there a limit to the source materials needed for the craft? Are certain tools or instruments no longer in production? When the craft relies on selling the end product, maybe the market for this product has dried up or demand has changed. Perhaps there is less interest in maintaining the craft among younger generations. If so, why is this the case? Only when we have mapped the threats facing a craft, we can start thinking about potential ways of protecting it. What protective measures are acceptable needs to be decided together with the Heritage Craft Communities. Is it possible to start using other source materials or instruments, or is this unacceptable? To what extent can the outcomes of the Heritage Craft be monetised, or patterns and products altered? These questions have no one-size-fits-all answers but need to be explored through intensive, collaborative work with Heritage Craft Communities.

6. Protection

To understand how a Heritage Craft can or should be protected it is important to understand the past, current and future threats facing the craft. Heritage Craft Communities are best placed to understand these threats. Is there a limit to the source materials needed for the craft? Are certain tools or instruments no longer in production? When the craft relies on selling the end product, maybe the market for this product has dried up or demand has changed. Perhaps there is less interest in maintaining the craft among younger generations. If so, why is this the case? Only when we have mapped the threats facing a craft, we can start thinking about potential ways of protecting it. What protective measures are acceptable needs to be decided together with the Heritage Craft Communities. Is it possible to start using other source materials or instruments, or is this unacceptable? To what extent can the outcomes of the Heritage Craft be monetised, or patterns and products altered? These questions have no one-size-fits-all answers but need to be explored through intensive, collaborative work with Heritage Craft Communities.

7. Promotion

In theory, anyone can promote a Heritage Craft. From opening a shop, either brick and mortar or online, to sharing products on an Instagram page, promotion can take many forms. However, as the example of the Shetland Wool Week shows, involving Heritage Craft Communities can be crucial for enhancing the impact of the promotion activities, both for the Communities involved and other interested parties, such as researchers and customers.

8. Enhancement

If you are used to working in a more traditional heritage field and deal primarily with tangible heritage, the idea of ‘enhancing’ heritage might seem a contradictory term. But since intangible cultural heritage is a living and evolving kind of heritage, a decision can be made to enhance it, or in other words, to further improve its quality, value, or reach. Our case studies of the Chios Gum Mastic Growers Association, Shetland Wool Week and Jaipur Rugs show that stakeholders like external parties, a research lab, an organising committee or a commercial company can help enhance a Heritage Craft by introducing new uses and products, a new market, new patterns or ways of working. However, in all of these cases, the Heritage Craft Community had to be involved in the process.

9. Transmission

How are the knowledge and skills related to a Heritage Craft transmitted? How does a Heritage Craft Community train the next generation? And who is allowed to hold certain knowledge or skills? When thinking about safeguarding a Heritage Craft, either by analogue or digital means, these are crucial questions. Firstly, these questions come back to ownership and respecting community knowledge and skills. But secondly, there is usually a very good reason why a Heritage Craft is being shared or taught the way it is. The process of teaching or training is inherent to the craft itself and therefore should be taken into consideration when developing any kind of educational resource about the craft. This does not mean an understanding of the craft can only be transmitted traditionally, but it does challenge us to find a middle ground that respects the traditional learning trajectory.

10. Revitalisation

Just as Heritage Crafts change and adapt, they can also fade or lose meaning and relevance for a Heritage Craft Community. It might not mean the community is no longer interested in the craft; in fact, they might still want to preserve it as a Heritage Craft. But at the same time, they might not have the time and energy to invest in maintaining the craft as it is, or once was. Freezing a Heritage Craft is a sure way for it to lose its meaning over time. For the same reasons, it is not necessarily useful to look back in time, through books and images, for example, and try to find the moment in time when the craft was most ‘authentic’. This is the opposite of revitalising. To revitalise a Heritage Craft, the Heritage Craft Community should be involved in a conversation about what the craft once meant to them, what it means now and what it could mean in the future. Which techniques must be kept or brought back? Where could machines be used to create a faster process, while maintaining the important heritage qualities of the craft?