Photo’s by Lotte Stekelenburg for Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

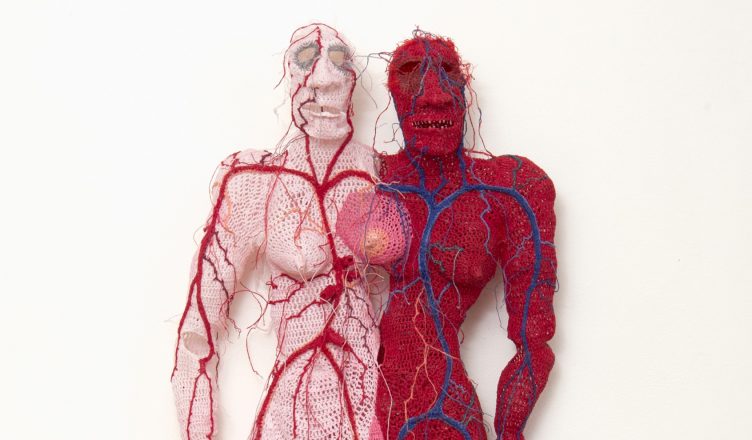

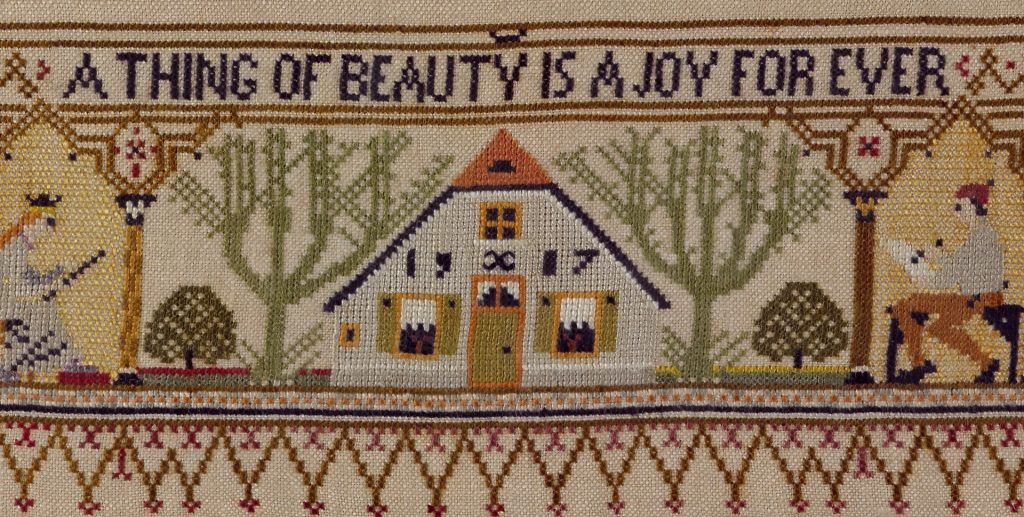

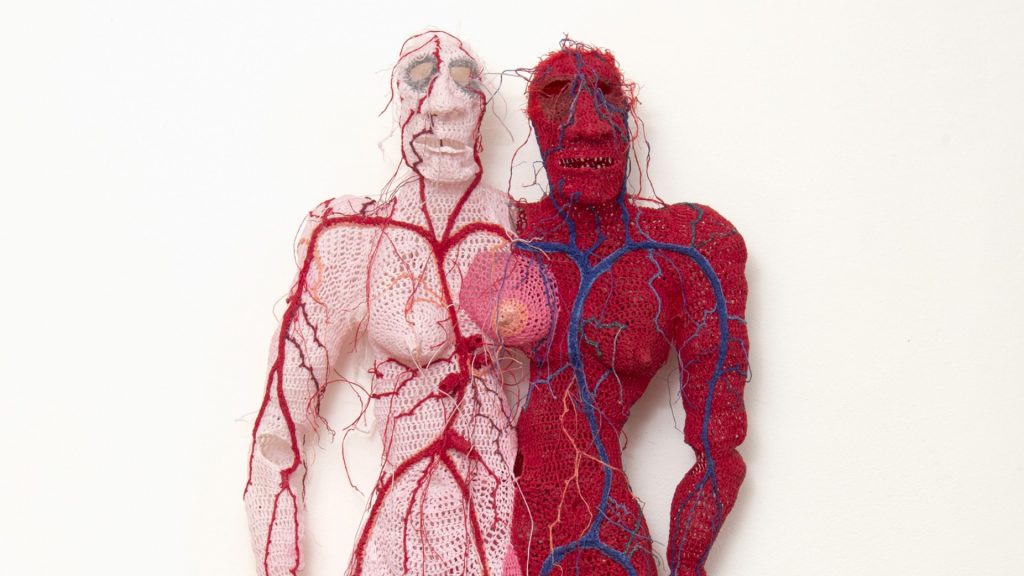

In the spring of 2013, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam hosted the exhibition Hand Made – Long Live Crafts, a concept by Mienke Simon Thomas, who works as senior curator at the museum. She wanted to show and celebrate craft in contrast to industrial mass production. Showing the production processes of the various crafts, as well as the way contemporary design is being inspired by these traditional techniques, was pivotal for the exhibition. Equally important was the intangible element of crafts and knowledge exchange. How could a contemporary art museum create an exhibition of making within the limits of an exhibition space? We spoke with Catrien Schreuder, then Head of Education and Interpretation at the museum, to find out more.

Bringing craftspeople into an exhibition space

The exhibition team did not want to create an environment that would only focus on the step-by-step production process. Craft is about skill, experience, personal preference, tradition and creativity. The exhibition should capture all these elements, as well as showcasing examples of contemporary design inspired by craft. As the exhibition concept was being developed, Catrien suggested physically integrating craft demonstrations into the exhibition. It would be the best, and maybe the only, way to do the crafts justice and meet the exhibition’s goals.

The exhibition curator had a large network within very diverse craft communities but finding craftspeople willing to work inside the gallery space was only one of many challenges the exhibition team faced. Work stations were integrated into the exhibition design, meaning there was no separate space to work in, but the physical work was done on the exhibition floor amongst museum objects and visitors. Craftspeople were invited to work in the gallery for a period of one week each during the opening hours of the exhibition, 11am – 5pm. A weekly changing schedule was made for six work stations, which proved to be a serious logistical challenge. The location of the workstations did not change. This meant that sometimes a craftsperson was doing work that was directly related to the objects surrounding them or relevant objects that were placed further away. As well as the demonstrations, some makers also gave workshops. During a crafts fair all kinds of craftspeople could sell their wares to museum visitors.

A few ground rules were identified when selecting makers. The craft process couldn’t be ‘wet’, meaning no liquids could be used in the gallery, and it couldn’t involve using gasses or flames. The use of sharp objects was considered out of bounds as well. These restrictions were challenging for both the exhibition team and the craftspeople. Some crafts are quite noisy, which also caused issues in the gallery space. Together with the makers involved, the exhibition team tried to find solutions to allow as many participants as possible to be part of the show. Sometimes this meant ‘pretend making’, leaving out any out of bounds tools, or a show-and-tell stall. However, the exhibition team preferred as authentic a craft experience as possible. Ideally, visitors would be able to join in, but in reality, this proved very hard to facilitate for most crafts.

A wide range of craftspeople was selected for the exhibition. This included professionals making a living with their craft, but also amateurs and even a group of elderly people living in local care homes who knitted the products of Rotterdam-based knitwear label Granny’s Finest. Some makers were scheduled for multiple weeks, because they really liked the concept and were available.

It quickly became clear that some makers had integrated giving demonstrations or workshops into their work practice. They felt comfortable engaging audience members, explaining their work and answering questions. Others had no such experience and at times found it challenging to be working in an environment where strangers would walk up to them and ask questions or comment on their work. This in return meant that visitors too would find it harder to approach these makers. Sometimes this meant that visitors didn’t quite understand what they were looking at or felt like they couldn’t ask any questions. Engaging a lay audience with your craft requires a very different skill set than performing the craft itself. Sometimes a craftsperson was particularly popular with visitors and their presence would be shared by word-of-mouth. Because each maker was usually only present for one week, this sometimes led to disappointment when visitors would come to see a specific craftsperson who had already left.

Creating partnerships

For most makers, their key aim was to reach a new audience, educate people about their craft and get them excited. The exhibition created a good opportunity to do this. It was important for the museum to truly integrate the working craftspeople in the exhibition, which ideally also meant involving them in the run-up to the exhibition. This was something the museum hadn’t done before and looking back two clear challenges can be identified.

First, the production time for an exhibition is generally at least 12 months. To ask people from outside the organisation to be involved from the beginning means reaching out to them and establishing connections early on. It also means claiming quite a lot of time from these people. Often, the craftspeople’s diaries did not allow the level of involvement the museum would have desired. The museum wanted to be more flexible to facilitate personal planning requests, but within the existing organisational structures this proved challenging. Those makers who had been more involved from the beginning would become a more integrated part of the exhibition than those who were later added to complete the rota.

Secondly, the conceptual and practical integration of the workstations needed safeguarding throughout the development of the exhibition. Once conversations with makers had started it soon became clear they needed more space to perform their craft than was initially planned. Simply providing a table to work at was not enough. Protecting this space for the craftspeople, both physically and conceptually, needed constant focus. How does one communicate about their presence and the fact that new people are at work every week? How can you best inform and guide visitors in an exhibition that allows for different kinds of behaviour than one is used to when visiting an art museum? The exhibition itself was more dynamic, but visitors too were invited to be more active. They were expected to engage with others in the gallery, something that’s unusual in most art exhibitions. Staff too had to adjust to this new gallery dynamic. Museum educators in particular had to respond to the everchanging presence of craftspeople and adjust their programme accordingly.

In the end, the presence of the craftspeople in the gallery was seen as an important element of the exhibition. Although videos could in some cases have provided a better explanation, nothing compares to the ‘magic’ of seeing somebody physically doing the work in front of you. Seeing somebody perform the same movements for hours on end in order to produce something, you see the focus and attention that are needed. These are things that cannot be conveyed via text labels or instruction videos.

Embedding what was learned

The experience gained during the Hand Made exhibition was put to use in following exhibitions. A good example is the exhibition Fra Bartolommeo The Divine Renaissance in 2017. The museum wanted to focus on the work process and contemporary relevance of this 16th century artist. The museum decided to invite a local artist, Iwan Smit, to set up his studio in the exhibition and work on a modern, contemporary altar piece, inspired by conversations with visitors. The museum now had a much better idea of the requirements and space that were necessary for a workable artist’s studio. They also knew that the artist they wanted to select not only had the artistic skills they were looking for in relation to the work of Fra Bartolommeo, but also needed a specific set of social skills to engage visitors. A stronger partnership was forged with the artist and his presence in the gallery was described by Schreuder like “an event, but spread out across three months,” rather than an element of a ‘traditional’ exhibition. The work Smit created during the exhibition was acquired by the museum and added to the collection. Schreuder further indicated that in her own practice, (she has since moved to Stedelijk Museum Schiedam) the idea of an exhibition as a dynamic space or workspace in addition to a space where people can look at objects, has become a recurring theme.

Could Hand Made have been a successful exhibition without the presence of craftspeople? Probably. But nothing compares to the thrill of seeing somebody using their mind and body to create a unique product, to witness the process and to realise: people still make things.

Based on an interview with Catrien Schreuder, Head of Exhibitions and Collections at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, former Head of Education and Interpretation at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, conducted on 7 June 2021.

Photo’s by Lotte Stekelenburg for Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.